Every month seems to bring another news report about North Americans relocating to Portugal… but almost none mention that just 100 miles northeast lies an exquisite slice of coastal Iberia that boasts all the same pull factors.

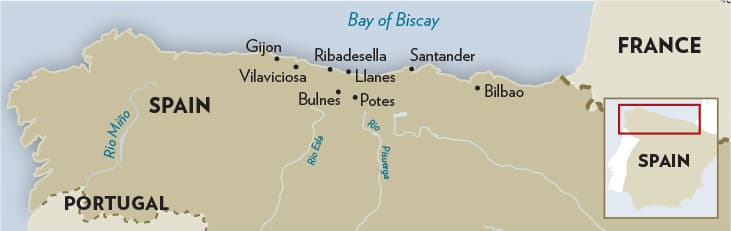

Let’s refer to it as Green Spain. Start at Bilbao in the north of Spain, then work westward to the handsome beach resort of Ribadesella. Within that 125-mile stretch, Green Spain gathers all the same ingredients that make Portugal so tempting: soft sand beaches, low cost of living, Iberian sunshine, and alfresco café culture.

Search for information about moving to Spain, though, and you’ll find a slew of reports and resources directing you to the Mediterranean coast, or to the ever-bickering sibling cities of Barcelona and Madrid. As for the north—Green Spain—it’s the information age equivalent of a blank space emblazoned "Here be dragons."

And so, in the spirit of pilgrimage-meets-quest narrative, I find myself behind the wheel of a rented Fiat 500 on the A-8 highway, white-knuckling my way between trundling 18-wheelers, suicidal teens on dirt bikes… and possibly even dragons.

I’m here to explore a forgotten section of Europe that delivers, well, pretty much everything.

My journey begins in Bilbao, an energetic port city reborn from its industrial past to a gastronomic, art-forward present. From Bilbao, I’ll bear west to the coastal towns of Llanes and Ribadesella. Either of those could be the ideal choice for adventurous expats seeking an affordable beach life in a relatively undiscovered part of Spain. From there, I’ll travel inland and explore the high mountain country of the Picos de Europa range.

Get Your Free Spain Report Today!

Get Your Free Spain Report Today!

Learn more about the lower cost of living in Spain and other countries in our free daily postcard e-letter. Simply enter your email address below and we'll also send you a FREE REPORT — Live the Good Life in Sunny, Affordable Spain.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.

Green Spain isn’t a hard and fast territory… it’s more of a way to put a name on the northernmost section of the country. Spain is divided into 17 administrative provinces known as Autonomous Communities. For the purposes of this article, we’re focusing on Cantabria, Asturias, and a little slice of Biscaya (since that’s where Bilbao is situated).

Green Spain offers a mild microclimate and fertile landscape that’s a comfortable alternative to the arid extremes found farther south. For the prospective expat, it’s a four-season wonderland of empty springtime beaches and shimmering russet falls.

Picos de Europa

What makes this region so special, and what makes Green Spain green, is the Picos de Europa mountain range. Vast limestone crags rise abruptly from the coast and reach elevations of over 10,000 feet in short order. The transition from beach landscape to highland forests is almost immediate as you head inland, and within five miles of the coast, knife-edge ridges and peaks overarch the winding road.

In comparison with the Alps, Rockies, or even the Pyrenees, the Picos de Europa is a tiny mountain range. From the eastern foothills at the stone-built farming town of Potes to the royal mountain retreat of Covadonga on its western edge, it covers just 40 miles. Even so, the influence on the local microclimate is immense. The peaks trap moisture from the Atlantic Ocean airflow, which then enriches the coastal plain with well-irrigated farmland and deciduous hillside forests. Average monthly temperatures range from 77 F in August down to 47 F in February.

Visually and culturally, it’s a stark contrast to the arid expanse of wheat fields, olive groves, and citrus plantations that typify the rest of Spain. In Green Spain, apple orchards, sheep farms, fishing villages, factory towns, mountain hamlets, and beach resorts clamor for elbow room in a temperate coastal strip.

Picture the Central California coast around Mendocino, but with jagged peaks rather than rolling hills, and you’re getting close. There’s a long, long continuum of settlement here. Europe’s oldest discovered cave paintings at Altamira—just inland from Ribadesella—suggest that Green Spain was as attractive to prehistoric dwellers 37,000 years ago as it is to present-day residents.

Bilbao: A Resurgent City

As accidental stage management goes, there are few sequences in the world that can compete with exiting the Artxanda-Salbe tunnel southward on the A3247 airport bus. I kid you not, I gasped. And I wasn’t the only one. When 40 hard-chattering Spaniards go silent in a collective intake of breath, the view must be special indeed.

Welcome to Bilbao. Please close your mouth now.

Bilbao will forever be associated with superstar architect Frank Gehry’s titanium-clad Bilbao Guggenheim Museum. Opened in 1997, in a (successful) bid to invigorate the city, the building is a pivotal data point on the timeline of post-war world architecture. Unlike a lot of statement architecture, though, it’s almost universally loved by visitors and residents alike.

The building’s polished exterior glares in the noonday sun and glows in the encroaching dusk. With an exterior form that simultaneously evokes fish scales and the outline of a container ship, its flowing, organic lines echo Bilbao’s maritime heritage. The structure is otherworldly… yet somehow appropriate to its surroundings.

Bilbao has had its periods of wealth and power. For centuries, it was the commercial, shipping, and banking hub of Spain. But by 1990, the city was a post-industrial casualty of globalization. Its economy—based on steel and heavy industry—was thrashed by Asian competition. The decline looked terminal, until an initiative to rebrand as an arts and tourism hub resulted in Gehry’s majestic Guggenheim.

It seems unlikely that the best view of it comes from the airport bus, but unless you have a helicopter, you won’t find better. On coming out of that tunnel, a natural cross-dissolve opens out to an elevated view of the brutalist La Salve bridge, the murky flow of the Nervión river… and the glittering starship angles of a building which changed the fortunes of a city.

The gallery brought huge levels of positive media coverage. Investment in trade and tourism infrastructure followed. The result: Bilbao is now one of Europe’s most urbane, intimate, and well-maintained cities.

Stroll along the river past art galleries, glass-fronted international hotels, and repurposed warehouse developments, or along the leafy neoclassical shopping boulevards around Gran Via, and you’d be hard-pressed to imagine Bilbao’s gritty industrial past.

Ride one of the silent, spotless trams from the Ribera food market by the old town to the conference centers and sports fields sector of San Mamés… and you have a cheap (€1.50 a ticket) sightseeing tour of the city’s finest parks, buildings, and river views.

Bilbao’s identity changes from neighborhood to neighborhood. The Casco Viejo (Old Town) is simultaneously touristy and residential, while always being energetic and pretty. Deusto, on the north side of the river, is studenty, with more affordable restaurants and bars.

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Sign up for IL's postcards and get the latest research on the best places in the world to retire. Including boots-on-the-ground insights on real estate and rental trends. Simply enter your email address below and we'll send you a FREE report - The World's Best Places to Buy Real Estate.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.

Gran Vía is upscale and exclusive, but within a few blocks becomes more eclectic, multi-ethnic, and decidedly more affordable as it nears Calle San Francisco.

(The area around Calle San Francisco was, until a couple of decades ago, considered to be edgy at best, dangerous at worst. These days, since a large police station was relocated there, it’s vibrant, family-oriented, and gentrification-ready. I saw a four-bedroom apartment listed for $149,000, which seemed like a steal. Nearby, in the central Indautxu neighborhood, low-rise apartment blocks cater to renters. A two-bedroom apartment with a balcony in this area of the city is available for €950 ($1043) a month.

Wherever you go in the city center, life is jolly, abundant, and alfresco. Basques—the locals of the Basque Country region stretching from Bilbao to the southeasternmost tip of France—pride themselves on having Spain’s finest cuisine (spoiler: every region in Spain prides itself on having Spain’s finest cuisine). They celebrate it by gathering at outdoor tables on every possible paved space.

Sometimes, the bar itself is nothing more than a tiny hall, kitchen, and a couple of restrooms, but the terrace out front might be serving 30 tables. Grab a pintxo or two (small portions of finger-food, like tapas only more elaborate, around €2 each), a glass of the sharp, lightly fizzy local wine—txakoli—and join the throng.

Though it’s not generally thought of as a coastal city, as the main city center is inland, be aware that Bilbao is less than 10 miles from the beach at Sopelana. In fact, for €1.90, you can take a metro train to Plentzia or Sopelana, both of which have fine cliff-lined beaches and amenities. Plentzia is sheltered and family-friendly. Sopelana is the rugged "surfing capital of Spain."

Both beaches are lovely, but if your heart is set on coastal living (or indeed, mountain scenery), the stretch from Bilbao westward to Ribadesella is surely one of the last forgotten sections of the southern European coast… and it cries out to be discovered.

Coastal Towns to Consider

Cider and Cuisine in Llanes

A 10-mile strip of flat grassland separates the beaches of the Asturias coast and the sheer walls of the Picos de Europa mountains. It’s good dairy country, and the sight of black-and-white Friesian cows meandering on the pale sand of a cliff-enclosed Asturian beach is commonplace.

Wildflowers grow in abundance. The scent of honeysuckle and wild rose mingles with the ozone tang of sea air. Much of this landscape seems more evocative of Ireland, Scotland, or maritime Canada than Spain… the cattle, the sea coves, the geometric precision of apple orchards backed by the fractal outline of peaks that pass for the Scottish Highlands.

Llanes is an attractive town of some 14,000 inhabitants, with a busy fishing/yachting marina, five magnificent beaches, a walled old town, and dramatic cliffs topped by a 19th-century lighthouse. Though it’s geared to the tourist industry, it’s also a local administrative hub, with a health center, veterinary clinic, supermarkets, railway station, and a municipal golf club (from €50 for 18 holes). Property prices are relatively high here due to the town’s reputation as an upscale location. A two-bedroom, sea-view apartment overlooking the marina currently lists for €205,000 ($224,000).

Renting in Llanes is a possibility too. A two-bedroom, ground-floor apartment in a modern building with a small outdoor patio area as well as access to a shared swimming pool and garage space goes for €550 ($604) a month.

Once a fortified fishing town, Llanes is now a fortified fishing town with a seasonal tourist industry, much of which is focused on the local beverage of choice: cider. If anything is the unifying emblem of Green Spain, it’s this mildly alcoholic apple brew (about 6% a.b.v.). It’s best sampled at a specialist sidrerías (cider bar), of which there are many. Sidrerías offer a range of traditional dishes—from grilled, buttered clams to charcoal-grilled beef rib steaks—to complement their flagship drink.

Cider is more than just a drink here; it’s a marker of identity. The rest of Spain is devoted to wine. Green Spain locals pride themselves on the fact that the climate here is better suited to the humble apple than the highfalutin prissiness of the grape.

Yep, there’s a culture wars element to it that goes way beyond beverages—northerners see themselves as hard-working, industrious go-getters, braving the seas and tilling the land, washing down the thirst of a long day’s toil with an honest tankard of cider. Those indolent wine drinkers in the rest of the country, the general feeling goes, spend half their day asleep and wouldn’t know which end of a pickaxe to swing.

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Sign up for IL's postcards and get the latest research on the best places in the world to retire. Including boots-on-the-ground insights on real estate and rental trends. Simply enter your email address below and we'll send you a FREE report - The World's Best Places to Buy Real Estate.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.

Regardless of all that, it’s a refreshing tipple, and I seek out a suitably rustic sidreria in which to partake. Llanes is full of options. I chose El Antoju, a place with wooden benches and barrels on the main walking street above the harbor, where a 24-ounce bottle runs to a shade under $4.

Accompanying dishes range from $10 to $30. El Antoju’s lack of fanfare is typical of this elegant, understated harbor town. I had a plate of nibbles that was the essence of Green Spain’s singular mountains-meet-ocean surf and turf cuisine. Three anchovy filets came from fish landed at the commercial fishing port of Santona, just 40 miles west. The slices of nutty Cabrales cheese at their base came from the mountains just 10 miles inland. The slivers of grilled and skinned red pepper that formed the middle layer were grown in the patchwork of neat backyard gardens which surround every village in the region.

The overall effect was magnificent: intense, balanced, texturally delightful, and wholly surprising. (For full disclosure, I’m usually a reluctant fish eater, especially of such stridently fishy a fish as anchovy). Sometimes, it’s worth stepping off your preferred gastronomic path. The results can be inspiring.

Seafood and Surfing in Ribadesella

I can’t quite understand why property prices in Ribadesella come in at around 25% less than in Llanes. Both towns are a similar size, proximate to a significant regional city, and within a couple of miles of the A-8 highway that serves as the transport artery of the Spanish Atlantic coast.

Both have a railway station, health center, supermarkets, harbor, and beaches. Both have thriving tourism industries, and are waypoints on the most popular route of the Camino de Santiago pilgrim trail. For centuries, devout Catholics walked the Camino in a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela’s cathedral, where the remains of the apostle James are said to reside. Nowadays, the trek (which has multiple routes through Spain, France, and Portugal, depending on your starting point) is as much a lifestyle pursuit as a spiritual exercise, and brings some 350,000 walkers to the region each year.

From an expat’s point of view, property prices are about the only significant difference between Llanes and Ribadesella. The rest is cosmetic. The coast around Llanes is perhaps a little more rugged with sheltered coves and rocky promontories.

At Ribadesella, the town’s main beach is a half-moon bay of soft sand and surfable waves nestled between two protective headlands. Quirky 19th-century neomedieval and Art Nouveau homes line the beachfront, where a railed pedestrian promenade runs alongside the length of the strand. Squint a little, and you could convince yourself that you were on the celebrated beach of La Concha in San Sebastían—one of Spain’s most exclusive neighborhoods. There’s a similar belle époque atmosphere. Ribadesella, though, is significantly more affordable than San Sebastian despite being only a three-hour drive away.

Two-bedroom homes in Ribadesella hit the market at just €122,000 ($133,280). That’s for an apartment in the center of town, rather than on the beach side of the river dividing Ribadesella in two.

That’s no disadvantage; the town is a buzzing spot, with a handsome historic center packed with late 19th century townhouses sporting the traditional wooden loggias (sunrooms) of the region, pedestrianized streets, and multiple town plazas with outdoor dining. Renting in Ribadesella is also a possibility. A two-bedroom apartment on the beach side of town, a 10-minute stroll from the water, rents for €575 ($631) a month.

Ribadesella pitches itself as the adventure sports capital of the region, and the evidence for that is everywhere on a bright Saturday morning. Camino walkers stride through town on their westward pilgrimage, kayakers paddle down the slow-moving Sella river as it widens to form the sheltered town marina, surfers longboard on the benign waves of the bay, and roof racks stacked with expensive mountain bikes punctuate municipal parking lots. From Ribadesella, the western spur of the Picos range dominates the southern horizon. It is a privileged location.

But to truly appreciate Green Spain, beach hopping won’t cut it. For the full experience, you need to head to the mountains.

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Sign up for IL's postcards and get the latest research on the best places in the world to retire. Including boots-on-the-ground insights on real estate and rental trends. Simply enter your email address below and we'll send you a FREE report - The World's Best Places to Buy Real Estate.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.

Into the High Country

For the first few miles at the lower reaches of the Picos, eucalyptus thrives. Originally a native of Australia, the plant didn’t arrive on the European continent until the 18th century. Planted and propagated in the temperate regions of the world, its hard, dense wood would have been ideal for building ships… except that shipbuilding graduated to iron and steel quicker than the slow-growing eucalyptus tree could fill the gap.

In the end, the primary use of eucalyptus on the Iberian Peninsula (the landmass that comprises modern-day Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar, and Andorra) is as a barrier to soil erosion. It’s particularly prevalent in northern Portugal, where it blankets the inland hills from Lisbon to Porto in deep blue-green folds.

Here in Green Spain, there is less of it than in Portugal, but it’s enough to scent the air with its sinus-clearing clarity as you pass through the lower slopes of the Picos. The effect, particularly with the bright Spanish sun glinting through the finger-like leaves overhead, is refreshing.

Splendid Isolation in Bulnes

At La Casa del Puente in Bulnes, the proprietor saves on utilities costs by cooling the bar’s stock of cider in the river out front. The Río Cares, which strongarms its way through the angular limestone of the Picos de Europa range, passes within stretching distance of the stone-built hostelry. Close enough that kitchen staff can lean over and drop a crate of bottles into the fast-flowing channel. Even in late May, it’s churning with snowmelt from the high peaks.

Given Bulnes’ natural beauty, it should be on a million bucket lists. It surely would be if it were better known. Until 2001, the neat stone village (pop. 34) was the most isolated in Europe—access was by hiking track only. Nowadays, you can visit Bulnes via a cable railway from the station at Poncebos village on the valley floor.

But even so, there is no vehicular access to the pristine little hamlet. No cars or trucks, no streets, no parking lots, no engine noise.

After 6pm, when the last funicular (picture a charmingly rustic trolley) of the day descends, a calm settles on Bulnes. It’s uncanny that within a couple of hours of the shopping streets of Bilbao such deep tranquillity exists. Locals tend to livestock and gardens, a few hikers sit at the outdoor tables of the bar, and the river’s roar is a constant soundbed.

It’s not silent, but the sense of calm has nothing to do with noise levels. It’s a feeling of being cozy in a remote location, far from the shrieking 24-hour news cycle, the chatbots, the traffic, the sirens. I work my way through a bottle of water-cooled Asturian cider and enjoy the post-hike burn from the rough stone track that brought me here.

But Bulnes does have amenities and comforts. The hotel where I spent the night—El Caleyon—was among the nicest I stayed at during my trip. A snug attic room, a bookshelf stacked with a decent range of English-language volumes, and the off-key clank of sheep bells from the paddock outside… it was all I could do not to doze the evening away in a post-hike miasma of content.

Instead, I headed to the main room/bar/restaurant downstairs and had a fresh-pulled espresso for €1.20. That’s the part I struggle to process: a captive market, supply runs by funicular, logistics to make an accountant weep… and yet the price of a coffee is the same as in the average Spanish town.

Get Your Free Spain Report Today!

Get Your Free Spain Report Today!

Learn more about the lower cost of living in Spain and other countries in our free daily postcard e-letter. Simply enter your email address below and we'll also send you a FREE REPORT — Live the Good Life in Sunny, Affordable Spain.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.

It’s not just coffee, either. A bottle of cider by the river cost €3.50, my evening meal of fabada and fresh-baked bread cost €12.50, and the room for the night (twin, breakfast included, with bathroom) went for just €75. The value is staggering. In any comparable location in the Alps or Pyrenees, you’d pay triple that.

Bulnes is an extreme example of what rural Green Spain has to offer… and it would be a rare expat who could settle here. For all the undoubted romance of living in a roadless farming hamlet surrounded by 10,000-foot peaks and sheep pasture, the reality of winter in such an isolated spot would be dark, cold, and dull.

Although there is electricity and internet in the village now, the staff of El Caleyon point out that storms can knock all that out in moments. Even in late May, a flash thunderstorm of hailstones effectively locked me indoors for the evening, and by morning a fresh coat of snow had settled on the upper peaks. Exquisite to look at from afar, but challenging on a day-to-day basis.

Those looking for the moderate version of Green Spain mountain life should consider one of the many farming villages lower down the mountainside. Small towns such as Potes (pop. 1,350) or Arenas (pop. 882) offer much of the same rural tranquillity, stone-built prettiness, and magnificent mountain views, but also provide such "luxuries" as vehicular access, medical facilities, and the chance to buy supplies after 6pm.

Smaller villages such as Sotres (pop. 130) bridge the gap to full country living. Alternatively, the countryside around the pretty medieval market town of Villaviciosa is studded with townlands, villages, and hamlets where a stone farmhouse on its own acre of land can go for less than €80,000. In the village itself, a one-bedroom apartment rents for €390 ($428) a month.

By local standards these are isolated properties, but nowhere on the northern side of the Picos is more than 20 miles from the beach or 70 miles from a sizable city.

I easily could have spent another few months exploring Green Spain and I’d still only scratch the surface. Bulnes, Ribadesella, Llanes, Bilbao—each is simply an example of the beach towns, cities, and mountain villages on offer. I could have chosen others—Comillas, Laredo, Santander—to illustrate the same points. While these aren’t established expat enclaves of the sort you might find in Costa Rica, Mexico, or Panama, if you’re adventurous and like the idea of settling into a local community, there are hundreds of spots to choose from.

Meeting other expats in Green Spain requires a little effort on social media, but is by no means impossible. Northern Spain Expat/International Community is a friendly group on Facebook. And while you won’t find clusters of expats in the countryside, Bilbao and Santander are both multicultural cities with diverse populations—you won’t be the only North American in the city!

If you’re serious about a move to Green Spain, it’s probably best that you brush up your Spanish skills. Cantabrians and Asturians speak Spanish as their first, and often only, language. Though you might come across English speakers working in the hospitality industry, it’s not as common within the civil service or healthcare sector, and the sort of English-speaking enclaves you might find on the Costa del Sol or Costa Blanca (traditionally popular with British retirees) do not exist here.

Spanish will serve you well in Bilbao, too, although do bear in mind that the Basque language is also used in the city and its environs. You’ll see it written on signage and posters, and hear its staccato rhythms in local bars. As a language, Basque pre-dates Spanish, and shares none of its vocabulary or structures. It’s worth learning a phrase or two out of respect, but for most people, Spanish is by far the easier language to learn and, ultimately, more useful. Full immersion in the community and culture quickly follows even a basic grasp of Spanish.

When you consider the payoff, it’s well worth the effort. Compact, but bursting with options, Green Spain deserves to be better known. It won’t be long before the region generates the same buzz among prospective expats that its n

eighboring Portugal did some 20 years ago.

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Sign up for IL's postcards and get the latest research on the best places in the world to retire. Including boots-on-the-ground insights on real estate and rental trends. Simply enter your email address below and we'll send you a FREE report - The World's Best Places to Buy Real Estate.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.

THE MENÚ DEL DÍA: HOW TO EAT LIKE A LOCAL

A cross between soul food and the dinner Grandma used to make, the Spanish menu menù del día, the set menu served for lunch, is designed to fill the bellies of workers on their lunch break, whether they’re in factory-floor overalls or bank clerk’s office wear. It’s cheap, filling, and decidedly unfancy.

That doesn’t mean that it’s low in quality, just that it’s food without pretension. Service is equally unpretentious. Expect your waitstaff to take your order politely and deliver it to your table, but don’t count on the zeal of tip-reliant North American servers. (In fact, a tip is not expected; if you decide to leave something, €2 is plenty.)

You’ll find menu boards displayed outside bars and restaurants, usually listing starter and main course options as well as the price. A chalkboard is a good sign; it suggests that the chef is preparing options according to what’s in season or what was available at the market that morning. (More permanent menu boards mean it’s likely you’ll be eating something that came out of the deep freeze.)

During my trip across Green Spain, I had menus that ranged from €24 at a fancy beachside fish restaurant in Santander to a delicious €10 range of choices at a Bolivian bar in Bilbao’s San Francisco district. Most options in Green Spain, though, were €15 or €16.

For that, you get a three-course meal with bread and wine included. Again, discard your preconceptions. Is the wine a single estate, barrel-aged symphony of velvety soft fruit texture with undertones of old leather and fine tobacco? Not at this price point. It will be a light-bodied young red, usually served cold and deposited without ceremony on your table. If there are two of you, you’ll usually get a full bottle. If you’re alone, you may get it in a smaller carafe. It still does the job admirably.

Be strategic in your choices. The main meat or fish option is saved for the second course, but be aware that it rarely comes with vegetables or greenery. If scurvy is a concern (and after a few days eating in Spanish restaurants, it will be), go for the mixed salad that will almost certainly be a first course option.

If more than one of your party chooses the salad, it will probably come on a large plate for you to divvy up family-style. This is important to know because if you’re having lunch with locals, any self-respecting Spaniard will immediately drench the plate with olive oil, wine vinegar, and half a pound of salt and begin mixing the whole thing up with a fork and spoon. The salad usually comes with a heap of tuna flakes, so if you don’t want a tang of canned fish in every bite, get in there quick before your local chum makes a cacophony of it.

Apart from tuna, you’ll find your salad consists of lettuce, sliced tomato, sliced onion, a couple of olives, and maybe a spoonful of corn kernels. At more expensive places, you’ll get the (dubious?) treat of a halved boiled egg on top.

In these regions of Green Spain, restaurateurs are deservedly proud of their bean dishes. Whether it’s fabada asturiana, pote de Cantabria, or the chickpea variation, cocido montanes, it’s rib-sticking good stuff.

There’s no set recipe, just the same way no two Louisiana grandmas cook an identical sort of gumbo, but you can count on at least one variety of dried bean or pulse slow-cooked to a silky, starchy softness, studded with smoky chorizo sausage, streaky ham cuts, or blood sausage… or all three. Soak up the juices with a torn hunk of artisan baked bread and wash it down with a draft of that cold red wine… and realize that you’ve still got two courses to come.

Personally, I like to fill up on the first course and then opt for fish in round two. Unless you’re paying top dollar, there won’t be as much bulk to the second plate, particularly if it’s a fish course. Breaded/fried hake, multiple fresh sardines (brace yourself if you’re not used to seeing fish heads as they’re left on in Spain), or a filet of steamed cod is typical here.

Meat choices generally include a pan-fried cut of beef, pork chop, or beef meatballs, with a few fries alongside. Dessert options are much the same wherever you go: yogurt, caramel flan, rice pudding, natillas (a vanilla/egg custard), ice cream, cheesecake, or a fruit tart. In most cases, these are commercially produced and brought in. But there’s almost always something that was freshly made in the restaurant kitchen, so ask "hay algo casera?" (anything home-made?), and choose that.

It suffices to say that by eating a menù del día, you are genuinely living like a local in Spain. Michelin-style dining it is not, but the act of taking an hour in the afternoon to eat at a down-home Spanish restaurant is a tradition instilled in the local culture.

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Free Report: Best Places in the World to Buy Real Estate

Sign up for IL's postcards and get the latest research on the best places in the world to retire. Including boots-on-the-ground insights on real estate and rental trends. Simply enter your email address below and we'll send you a FREE report - The World's Best Places to Buy Real Estate.

By submitting your email address, you will receive a free subscription to IL Postcards, The Untourist Daily and special offers from International Living and our affiliates. You can unsubscribe at any time, and we encourage you to read more about our Privacy Policy.