Not every country in the world is a good option for a comfortable retirement or relocation. In fact, the majority of them aren’t.

Please don’t read that as scorn or contempt for the huge range of astonishing sights, experiences, and people that are to be found around the globe; it’s not meant that way. Seeing Angel Falls and the white shard of K2’s summit are high on my list of wonders, but I have no intention of settling down to an expat life in either Venezuela or Pakistan. Some places are good to live in, some are good to visit, and a few are good for both. Ecuador is one of the latter.

Let me qualify that statement a little, though. Ecuador is not a small Caribbean island in which the expat experience is centered on poolside cocktails on the manicured lawns of gated compounds. And, while it has locations in which a large number of North American expats can be found, Ecuador has no equivalent of Spain’s Costa del Sol or Mexico’s Lake Chapala, where international residents can, if desired, exist in a bubble that’s entirely insulated from the local culture.

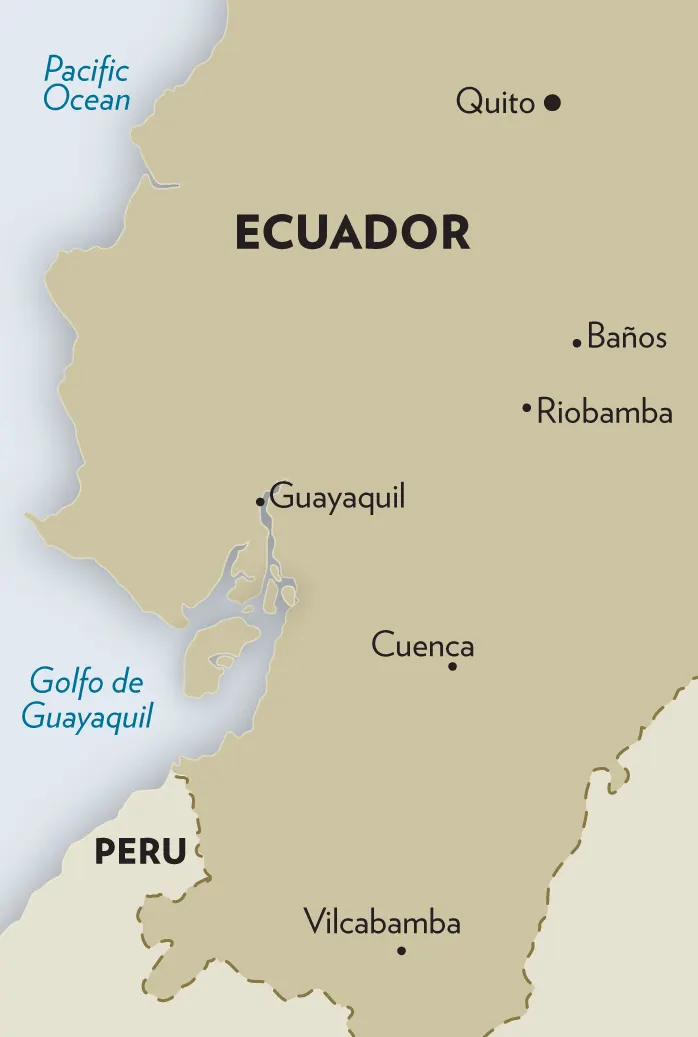

Even in towns and cities such as Cuenca or Vilcabamba—both established expat hubs—the dominant feel of the place is Ecuadorian; not homogenized international or North American. You’ll hear a lot of English spoken in Vilcabamba, but a lot more Spanish.

The landscape, too, is different from other popular expat destinations. This is worth recounting in some detail, because, while the imagery that usually goes with the expat dream often involves white-sand beaches, yachts, blue skies, and brightly colored afternoon beverages, that’s not the Ecuadorian picture at all.

Ecuador’s beaches, for example, are mostly vast, ocean-scoured expanses of hard-packed sand, interrupted by jagged stone outcrops and backed by high cliffs. They’re populated by scuttling crabs; overflown by pelicans, petrels, and frigate birds. The Pacific coastline of Ecuador is dramatic and vigorous, rather than languid and pretty.

As it happens, Ecuador’s coastline wasn’t my focus on this trip. It’s a worthwhile preamble though, because that vastness, that grandeur of landscape, continues inland. Journeying between Riobamba and Cuenca, for example, it’s immediately evident that, apart from the Himalayan massif, there is no higher place on the planet.

Peaks recede to the horizon in all directions. Some are topped by clusters of village buildings, but more often the mountaintops are unadorned green angles fading into a bluish haze. Roads are few, and those that there are snake tortuously up and down steep switchbacks.

Between Quito and Ambato the high plateau is level enough, with almost unbroken ribbon development built on both sides of the highway, but south of that point, whether toward the verdant horticultural slopes around Baños de Agua Santa (referred to as simply Baños) or higher into the dry mountain tundra of the páramo toward Cuenca, settlements become sparser and less frequent.

Aside from the bigger towns—Riobamba, Baños, Cuenca, and Vilcabamba—there is little to interest most expats in the subsistence villages of the high Andes. Dramatic mountainous backdrops, handsome Spanish colonial architecture, excellent hiking, and colorfully dressed indigenous peoples make for rewarding daytrips and photo opportunities, but unless your ambition is to retreat from the modern world and derive a living from the land, it’s probably better to base yourself in one of Ecuador’s established expat hubs.Eating out can cost as little as $2.50 for a set lunch.Those hubs can be a surprise, amid the vastness of the rural Andes. The degree of change, from windswept tundra to cozy valley, is profound. Each of them has a particular character and distinct setting. Riobamba is stately and proud of its status as the city in which modern Ecuador was founded. It’s higher and cooler than the others, with a dramatic mountain backdrop. Little Baños, on the other hand, is the party town of the mountains, catering to weekend travelers come to kayak, climb, bathe in its hot springs, and dance the night away in its clubs. Vilcabamba is the quintessential Latin American village, focused on its bright church and leafy plaza, with jungle-clad slopes rising steeply from the valley floor. It’s the epitome of an easy-living idyll, snug and comfortable after the stark drama of the high mountain plain.

That same comfort is most notable in the city of Cuenca, where the intricate beauty of pristine Spanish colonial architecture is home to galleries, museums, restaurants, bars, and theaters of international repute.

Squint a little in Cuenca and you could convince yourself, as a quiet electric tram eases its way down Calle Gran Colombia, that you’re in Bilbao. And yet, there are details that are specific to this place alone. The Tomebamba River, which flows through the historic center of the city in a delightful line flanked by willow trees, jacaranda blossom, and a pedestrian walkway through its banked lawns, is crystal-clear, without a shred of litter.

WHY YOUR DOLLAR STRETCHES SO FAR

Ecuador is a developing country. Think about its $400 per month requirement for a retirement visa. The figure mirrors the country’s minimum wage. It’s worth stopping to think about that. Four hundred dollars per month is what’s considered necessary to live a reasonable life in Ecuador.Think in terms of $50 a week to feed a couple.If you can manage to do without imported luxuries and do your grocery shopping in the daily markets, like locals do, it’s simply astounding how far your dollar stretches (and it is a dollar—Ecuador uses the U.S. dollar as its currency). Think in terms of $50 a week for fresh fruit, vegetables, dairy, and chicken or pork to feed a couple.

Eating out can cost as little as $2.50 for a basic almuerzo set menu. That’s usually a starter of soup, followed by a main course of grilled/fried slice of beef, pork chop, or fish fillet. A drink is usually provided. Nothing fancy, just a fruit juice, but I’ve had some lovely home-made limeade with almuerzos.

One nice aspect of the almuerzo is that it’s not a phenomenon that’s confined to street food shacks or the plastic seat places you find in markets (although those are really excellent, affordable places to enjoy hearty local cuisine). Better restaurants—the kind with tablecloths, ambience, and wine lists—often offer a lunchtime almuerzo too.

At the upper end of the dining experience, larger towns and those geared to the tourist trade always have more upscale offerings. Cuenca, in particular, is a well-served city in terms of drinking and dining options, with a recent renaissance in the craft brewing industry giving fresh legs to the nightlife repertoire of the city. Expect to pay North American prices for that, though.

The other side of that affordability, however, is that many, many Ecuadorians survive on incomes that can only be described as paltry. While the Spanish colonial architecture of Ecuador is beautifully restored and maintained (better maintained than in many Spanish towns I’ve been to), and while every city has its genteel, middle-class sectors where expats and well-heeled Ecuadorians live, it’s true to say that between the two, there are areas where you will be confronted with extreme poverty and its effects.

People who subsist on $400 a month have bigger concerns than keeping their homes freshly painted, or their gardens watered, or even having windows on the second floor of their building. In the rougher parts of towns, curbs are crumbled, huge clusters of overhead cables hang low from telegraph poles, and stray dogs loll on dusty corners while loud traffic belches unleaded gasoline fumes.

Nevertheless, although you’ll encounter poverty in the low-rent areas of major towns and cities, it’s not accompanied by a high crime rate or resentment toward foreigners. In general, distant curiosity at a gringo out alone is the predominant reaction I’ve been subjected to, rather than any hostility or danger.

In my experience, the expats who make the most successful lives in Ecuador involve themselves in some sort of voluntary activity—whether it be horseback riding with disabled children, organizing housing projects in disadvantaged areas, fundraising for orphanages, or getting involved with animal charities. I’ve met expats from La Libertad to Baños, Quito to Cuenca, who have vastly improved their own social lives, integrated with their community, and made a positive difference to their adopted hometowns in this way, and they all report happier lives because of it.

The city’s market hall is scented with the aroma of hog roasts and palo santo smoke, and the local people, whether you’re asking for directions or purchasing supplies, have a courteous, trusting manner that’s almost extinct elsewhere. When I bought an electrical adaptor at a hardware store in Cuenca’s historic center, the store clerk didn’t have change for the $20 note I offered. He gave me the item anyway, content to wait until later in the day when I had smaller bills. When I rented a bike in Baños, there was no need for I.D. or a deposit. “Just bring it back when you’re finished,” the attendant explained.

That unguarded, trusting nature is the true advantage of Ecuador, and something that every expat I spoke to in the country cites as one of the reasons they love it there. One example stands out as an illustration: at an unpretentious restaurant I visited in Loja, I ate a $2.50 almuerzo meal of hearty potato and bean soup followed by a pan-fried turkey breast served with a small salad and puréed potato. That’s pretty standard for an almuerzo—the set lunch option you see all over the country. The food also came with a drink; in this case, a glass of fresh-pressed sugarcane juice.

As she filled my glass from a jug, the waitress encouraged me to take a sip. I thought she was asking me to taste it. In fact, she was explaining that if I made a space in the glass, she’d top it up. There was, after all, still some juice left in the jug, and I might as well have it. I learned later that this concept is called la yapa in Ecuador and is an integral part of the culture. It’s the little bit extra—whether it’s an additional mango added to your bag after you’ve paid at the market, or a spare set of laces thrown in with a new pair of shoes.

The yapa is as good an illustration of Ecuadorian friendliness as the young student who, on seeing me lining up a photograph of the Tomebamba, walked me to a nearby spot with a far better view. It’s easy to describe Ecuadorians as “old-fashioned,” but that’s patronizing. Ecuadorians are no less modern than people anywhere else, and you’ll find malls, KFC franchises, iPhones, and Netflix in all the main towns. It simply seems that they’ve managed to absorb the influences of the post-internet world without losing courtesy or human grace.

But something new about Ecuador right now is that expat life there is experiencing a transition, and one that makes it even more attractive to energetic, active types who see relocation less as an opportunity to retreat from the world and more as a chance to reinvent and reinvigorate their lives. I spoke to numerous retirees in the country, and they all impressed me with their hands-on involvement with volunteer groups, business ventures, or outdoor activities.

What I hadn’t expected, though, was the number of younger expats who have recently moved to Ecuador, many of them in their early 40s, with school-aged children. That influx of younger expats—the digital natives for whom the traditional restraints of location on career are of no concern—may prove to be an interesting influence on Ecuadorian expat life.It’s so easy for people to set up businesses here.Take Kanell Lamont, for example, who moved from California to Cuenca in July 2019 with his wife, Shannon Baker, and their two girls, Shanell and Shareese. “It’s so easy for people to set up businesses here,” says Kanell. That’s partly because Ecuador’s government, in the wake of COVID’s impact, has encouraged small businesses. “It’s very possible to make money as an entrepreneur here,” Kanell continues.

The project he’s currently working on, TASTE Ecuador, gathers Ecuadorian chefs and food producers to focus attention on the country’s excellent foodstuffs—from tiny pink bananas through to excellent native shrimp—and bring them to a worldwide market. It’s the type of niche in which an energetic outsider with a fresh perspective can excel in a country which has, to date, had minimal impact on the international food scene.

Recently arrived expats like Kanell and Shannon are bringing a new energy to Ecuador’s international community, seeing opportunity and promise in their new home. They’re the next pioneers in a country that saw a proportion of expats leave in 2020, largely as a reaction to the global pandemic. Those who stayed, and those who have recently arrived, tell stories of a country which is ripe for rediscovery. Things have reset, if not quite to zero, then back a few notches. I won’t claim that the country has emptied out entirely, just that there aren’t as many expats as before, meaning that there’s not as much competition for the best accommodation as there once was, not as many gringo faces as you walk around town, and, best of all, not as much expected of prospective expats as they apply for visas.

To explain that final point, it’s worth noting that the government of Ecuador truly welcomes, and wants, expats. When the flow of retirees to the country began to weaken in the middle of 2020, the Ecuadorian government took steps to encourage them once more. The approach taken was to cut the minimum monthly guaranteed income required for a retirement visa to just $400 a month.

Put simply, that makes Ecuador one of the most affordable destinations to retire to in the world. For comparison, consider that the minimum requirement in Thailand or France hovers around $2,000 per month, per person. The figure varies from country to country, but even before the virus, Ecuador set its requirement at just $800. Now, at half that, it’s a remarkable option for retirees (and it’s not just for seniors; to qualify for a retirement visa, you need only be over 40 years of age).

While in the incredibly beautiful city of Cuenca, I spoke to Sara Chaca, an attorney who specializes in Ecuadorian law as it applies to expats. Sara pointed out that the current rate of $400 a month was set as a response to the pandemic. When that passes and the flow of expats gets back to full speed, it may be revised upwards, but even so, the prior figure of $800 a month is within the means of most Western retirees.

CHOOSE YOUR SPRING-LIKE CLIMATE

On this occasion, my destination was the mountainous spine of Ecuador, also known as the Avenue of the Volcanoes. It’s a route that follows the high Andes south from the capital city, Quito, down to the subtropical valleys of Vilcabamba at the bottom of the country. The steepness of the slopes combined with the year-round sunshine of this equatorial region, means that average temperatures fall with every increase in elevation, and picking the climate that suits you best is as simple as finding the town or city that lies at the desired altitude.

This really is the case—I’ve heard the phenomenon described on many occasions, in relation to locations in Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Mexico. That said, it’s uncanny to experience it in the flesh, to really get a feel for how marked the change is and how quickly it can take place.

Take, for example, a bus trip I took from the high-altitude town of Baños to the nearby market town of Puyo in the Amazon basin. The bus tracks a deep valley via a section of highway known as “the route of waterfalls.” It’s an apt name; the high sides of the valley are punctuated by vertical whitewater cascades of anything up to 100 feet high. Within the first 10 miles or so, the vegetation consists of pine trees, eucalyptus, camellia, and sheep-mown grass.

Another 10 miles on, and the pines thin out, replaced by coconut palms and clustered fig trees. Elephant grass creates a shoulder-high curtain along the roadside, broken by occasional spiky outcrops of aloe vera and yucca. The river widens, the valley sides flatten out, and in the darkness of tropical forest an occasional flash of bright color signals the flight of wild parrots.

All this change takes place more quickly than your senses can fully process it. But when you descend from the air-conditioned bus in the light jacket that was comfortable in Baños, a hot waft of humid, 90 F air hits you, immediately making anything but the lightest clothing superfluous. It’s a huge change in less than an hour’s travel, but it’s worth noting just how closely packed the microclimates of Ecuador are. It’s one thing to describe a town or city as having a “spring-like” climate year-round, but when you get to these high places, it quickly becomes clear that spring-like is a relative term.

For example, the weather in Cuenca while I visited was gloriously bright, clear, and sunny every day from dawn until noon. About then, the sky hazed up, thickening to full cloud cover by around 4 p.m. By nightfall, at around 6.30 p.m., temperatures dropped from a daytime high of some 75 F right down to the low 50s F. I’d brought a down-filled jacket with me on the trip and was glad I’d done so.

Three hours south of Cuenca, Loja sits at a lower elevation and is markedly warmer. Daytime highs stay stable at around 77-78 F, and nights require nothing more substantial than a cotton jacket or sweatshirt. Farther south again, to the pretty village of Vilcabamba, and it’s just a little bit warmer still. You’ll see lime trees growing next to coffee bushes and huge date palms in full fruit.

In all four places, Cuenca, Baños, Loja, and Vilcabamba, expats will tell you that they live in the place with the best climate in the world. And in all three places, they’ll use the phrase “spring-like.” For each of them, it’s absolutely true. My point? Take very seriously the microclimates of Ecuador and spend time deciding on what your ideal climate is. In terms of temperatures at least, finding the one that suits you best is entirely possible. Just be sure to narrow it down further than “spring-like.”

Something else to note is that Ecuador is among the most affordable of all the destinations IL reports on. On my trip I spoke to one Canadian couple, Sharon and Kenneth Taylor, who reported paying just $350 a month for their three-bedroom condo and who even knew of a two-bedroom apartment that was available for $250.

Bear in mind that this was not in some one-horse village with dirt roads and intermittent electricity supply. We were in Loja, a sweet university town in the south of Ecuador, with perfectly maintained streets overlooked by the wrought iron balconies and wooden eaves of 18th-century townhouses and surrounded by the deep green peaks and terraces of the Andes mountains.

Even in the leafy, upscale districts of the capital, Quito, rents are affordable. Donna Hilden, who moved from Naples, Florida in 2017, shares a three-bedroom home with her adult daughter in the Metropolitano sector of the city, for which they pay just $575 a month. Donna fills her retirement with horseback riding, volunteering, and teaching informal English lessons to her students as they walk through the city’s parks. Melanie, her daughter, teaches music at an international school and fills her free time with alpine climbing and mountain biking excursions.

For both of them, Ecuador is much more than simply an affordable place to live, it’s a place where they can expand their personal frontiers and live the life that fits their personalities better than the work-obsessed rat race of North America.

“It’s been a real adventure,” Donna says of her move to Ecuador. Melanie agrees, noticeably impressed by the transformation she’s seen in her mother: “I’m really proud as a daughter,” she says. “My mom has become so flexible and adaptable as a person. It’s opened up her worldview.” As we weave through busy city traffic in Melanie’s rugged, mud-spattered four-wheeler on my way to Quito’s bus station, it’s heartening to see this intrepid mother-daughter combo so stridently building fulfilling expat lives with laughter and camaraderie. Their lives, on their own terms. South America has always been synonymous with adventure, reinvention, and exploration. Ecuador excels in providing all three, but its particular magic is that it does so with such comfort, variety, and grace.